Dark psychology in UX: The subtle art of making users addicted to your product

Making a habit out of a product

Do you ever feel like someone’s pulling your strings while you’re using an app or service? Like you’re interacting with the product almost without conscious effort or need to do so? Checking it on your phone or desktop almost compulsively?

You’d certainly be able to name at least five main culprits—corporations that are often accused of inducing these behaviors. And there are many, many more, because these days, a company needs to do much more than just very conspicuously exist to really hook a user, since we’re all constantly bombarded with various distracting attempts at grabbing our attention.

So, it should be more than obvious by now that companies employ little psychological tricks and devices here and there to reinforce behaviors beneficial to them. They can range from seemingly innocuous, like gamifying your attempts at learning a language by giving you level-ups and badges, to more nefarious examples like shaming you and making you feel bad for trying to opt out of a service you no longer want to use.

But the real winning move is getting the user to form a habit around their product. When the user keeps having the urge to use this product without there being a direct stimulus from the product calling for the user’s attention, that’s when the company knows they really got them—hook, line, and sinker.

How very clever. Well, doesn’t this sound a bit manipulative to you?

Dark patterns in apps and services

Sounds about right, then. As long as there’s been incentive to keep as much user attention on one’s digital product as possible, there have been ways to get this through questionable means—which we now collectively call dark patterns.

If the name “dark patterns” instantly makes you think of the dark triad in psychology, well, the parallels are certainly obvious. They’ve both got to do with manipulative and socially undesirable behaviors.

Certain psychological principles can be leveraged in dark patterns in UX design to manipulate or deceive users into taking actions that may not be in their best interest. The aforementioned shaming when trying to opt out of a certain service, or confirmshaming, is a clear example of this, and is often listed as a kind of dark pattern. This way, a user ends up manipulated by having their emotions used against them, making them stay with a service that they’re not satisfied with, which ultimately benefits the company.

There are other examples. There’s a really “fun” one called the roach motel, in which a user’s path to subscribing is made to be as easy as possible, but getting out of the whole deal is a convoluted nightmare designed to make you give up and continue with your usage.

Then there’s nagging, with constant reminders or pop-ups to urge you to take a particular action, if only just to remove the nuisance. Scarcity illusions are another often-seen example, where a webshop might create a false sense of urgency to pressure you into making a quick decision to buy something that you might actually pass on were you to consider it for a longer amount of time.

And there are many, many others. But nothing quite comes close to deliberately making your product someone’s habit. While maybe not a named dark pattern per se, you can’t deny that making a user practically addicted to a product is a rather nefarious thing to do. And the reason it works especially well is this thing called intermittent reinforcement.

Why does it work

To really make sense of what intermittent reinforcement really is, we should first talk about the processes and mechanisms that make it work the way it does.

First and foremost, the dopamine system plays a big role. Dopamine, the “feel-good” neurotransmitter, operates within the brain’s reward circuitry and compels humans to constantly seek rewards while inducing a semi-stressful desire state. This desire state, characterized by an insatiable longing for the next reward, makes humans incessantly seek gratification, and this in turn forms the basis of compulsive behavior—repetitive actions in anticipation of rewards.

So, the dopamine creates a push-and-pull between satisfaction and an itch for the next reward. However, something that B. F. Skinner, a psychologist and the father of Behaviorism, discovered in his experiments is that spamming the test subject with rewards every time they expect one is not nearly as enticing as giving them a reward only sometimes, and irregularly at that.

Yes, turns out less is more and unpredictable is better, because humans seek predictability but are intrigued by variability, and sporadic rewards therefore light up our brains like a jackpot.

How to keep users hooked

Intermittent reinforcement as a term in behavioral psychology therefore stands for a variable schedule of rewards that instigates compulsive behavior. B. F. Skinner identified this as having to do with the notion of operant conditioning which he studied extensively: the idea that behavior is influenced by the consequences that follow it.

Have you ever bought booster packs for a trading card game? Each pack means a certain chance you might get a rare or desirable card, though the outcome is, naturally, up to luck. But the unpredictable nature of it all makes you buy more packs in the hopes of getting those special cards. This randomness and the anticipation of a reward with each purchase creates a compelling, sometimes addictive incentive to continue buying packs.

Of course, the occurrence of a reward in the form of a rare card is based on luck for the buyer, but there’s a calculated randomness to it made by the company so that there’s an average rate. The rewards don’t need to be based on chance, though. Intermittent reinforcement has several defined schedules, namely Fixed Ratio and Variable Ratio, as well as Fixed Interval and Variable Interval; these are variations regarding either the consistency or randomness of giving out the reward based on the number of responses, or the amount of time passed.

Consistency and randomness aside, the main thing is just to make sure the desired behavior is not rewarded every time it happens, as this maximizes addictiveness and compulsivity.

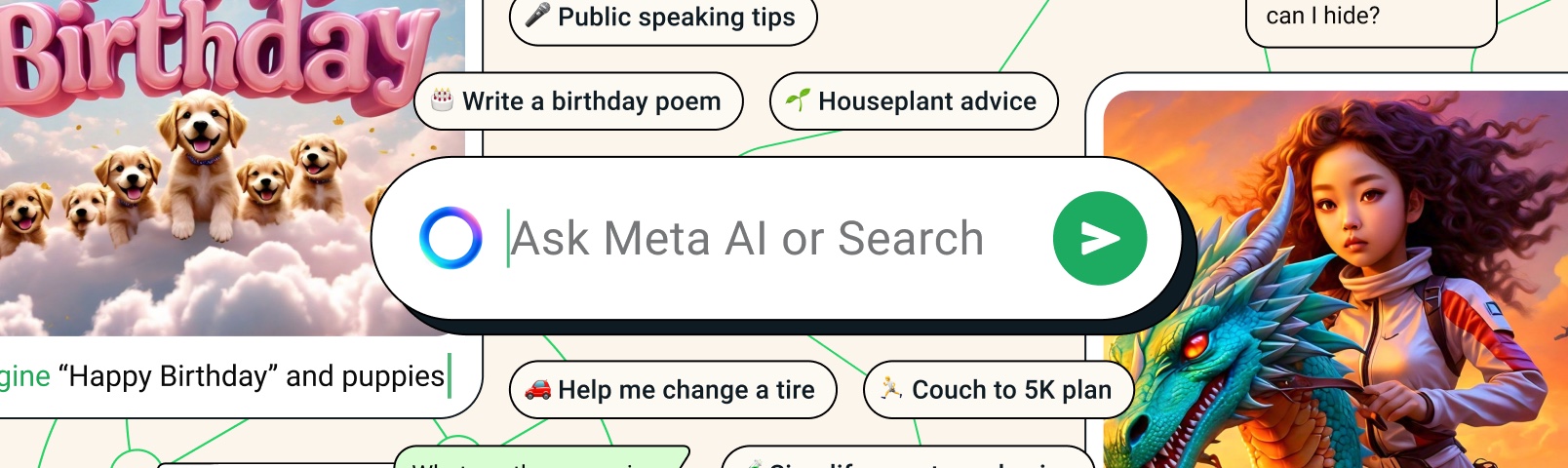

Intermittent reinforcement in UX

When it comes to UX design, there are obvious practical applications of operant conditioning such as intermittent reinforcement. Designers can (and do) use intermittent reinforcement to create engaging user experiences—for better or worse.

For a really blatant example, gambling websites use intermittent reinforcement through unpredictable rewards to keep people gambling. This is nothing new, of course, because real-world casinos operate on the same principle.

To make a parallel with booster packs from before, loot boxes in video games are another good example of this kind of intermittent reinforcement in a digital product. They similarly provide random rewards when opened, and it pushes players to purchase or earn more loot boxes in hopes of getting a desired item, even though the outcome is uncertain.

Loot boxes are widely considered evil, so much so that there are talks of them becoming severely restricted or even banned in the European Union. But intermittent reinforcement in digital products doesn’t have to be straight up vile. Here’s a rather more tame example; there’s a newsletter that puts a hidden star emoji somewhere in the content. When the user clicks on it, they get an entry in a giveaway organized by the newsletter. The newsletter thus incentivizes interacting with it, and the user does so in the hopes of winning the giveaway. Nothing too bad, right?

Between the “please read my newsletter and you might get a prize” and the “get addicted to gambling so I can have your money,” there’s a whole murky spectrum of shady grays, and many of them are found in e-commerce. Here we have tricks ranging from rewarding customer engagements (like reviews, referrals, or social media shares) on an unpredictable schedule to promote more interaction, all the way to sporadically offering discount codes or special offers to users as they browse or make purchases to encourage more spending and browsing. Pretty much more of the same idea—you get the picture.

Dubious means for maximum profit

The pervasive use of psychological strategies, particularly dark patterns and intermittent reinforcement, in the design of digital products is obviously ethically concerning, to say the least. Deliberately implementing all these tactics and exploiting the dopamine system to make a product a habit seems to be quite a relentless trend in the tech industry. Sure, capturing and retaining user attention is the name of the game, and the competition is decidedly cut-throat—but does that really justify going all machiavellian with the means?

Consumers have every right to be aware of these tactics, so that they can make informed choices about the products and services they engage with. We as designers surely have a certain deal of power in shaping user behavior and experiences, even if we’re not always in a position to directly influence all the decisions regarding a product’s design. But we should definitely be striving to make a balance between creating engaging user experiences and respecting user autonomy and well-being if we want the digital landscape to be transparent and sustainable in the long-term.