There is no UX/UI, there is only UX! … Or is there?

The neverending UX/UI story

As I’ve recently been reminded during many online conversations, few topics in design generate as much discussion and debate as the relationship between UX and UI. And, depending on whom you ask, UX and UI are either wholly separate, overlapping, or UI is considered a subset of UX.

Turns out, it’s all very far from being a mere black-and-white scenario. Who would’ve guessed, right?

Due to the fervent opinion-sharing it always sparks, as well as it not having a definite answer, this topic reminds me in many ways of the age-old argument regarding form vs. function so prevalent in virtually all design branches. And this argument again echoes at times throughout the UX/UI (sorry, UX) debate as well, as it is used by some to demarcate designing for visual impact as opposed to designing for user needs.

At first glance, you might assume that the question of UX and UI being integral or separate needs no further discussion than this: it all boils down to context, situation, project goals—basically, the ever-elusive “it depends”. And you’d be right.

Or would you?

Since I’ve been a part of this ongoing discourse time and time again, it made me ponder why the question persists as it does, and why it even matters so much. So, naturally, I decided to have a go at it and submit my own musings to the neverending slew of posts and articles about the topic at hand.

Maybe the whole thing needs a different type of approach or perspective. There’s going to be some philosophy, and probably some psychology thrown in for good measure.

UX and UI—separate or overlapping?

Defining and explaining UX design as an industry has been a persistent challenge. Job titles like the infamous “UX/UI designer” reflect (and, in turn, spark) the ongoing debate about the separation or integration of these roles. Seems like all attempts at a useful distinction have been largely unsuccessful, which kind of emphasizes the messiness of the field of design as a whole.

So, let’s pinpoint the debate surrounding UX and UI as revolving around whether they are separate fields or overlapping disciplines. Arguably, UX is primarily concerned with empathy and user needs, while UI focuses on creating aesthetically pleasing and intuitive interfaces. Some people contend that both should be the responsibility of a single designer, while some argue for distinct roles. And the whole distinction is yet increasingly being questioned in favor of a holistic approach to design.

Before we really get into it, I think I should lead with a simple explanation of the relationship between UX and UI as stated by industry leaders and pioneers Don Norman and Jakob Nielsen. According to them, UX encompasses all aspects of the end-user’s interaction with a product or service, while UI focuses on the tangible interface that users interact with. To directly quote from NN Group:

“In order to achieve high-quality user experience in a company’s offerings there must be a seamless merging of the services of multiple disciplines, including engineering, marketing, graphical and industrial design, and interface design. It’s important to distinguish the total user experience from the user interface (UI), even though the UI is obviously an extremely important part of the design.”

Okay. So what the heck does that mean?

I find it interesting that people take this quote at face value. Call me crazy, but I read this as both acknowledging that UI is a part of UX, and stating they are separate. And then there’s another ambiguity there regarding distinguishing UX and UI as separate fields—or maybe it’s just them addressing the common misunderstanding that UX and UI are the same thing.

I don’t know, maybe it’s just me.

To the best of my knowledge, neither Don Norman nor Jakob Nielsen has made an explicit, standalone statement that neatly defines the relationship between UX and UI in the way that many in the design community probably hope for (even though their work provides ample context to infer that their approach to design is foundationally holistic). This makes sense, since both Norman and Nielsen have been in the field for decades, and their work spans a time when the distinctions between terms like “usability”, “user interface”, and “user experience” were not as clearly defined or as widely discussed as they are today.

Problem-solving under the UX umbrella

So, because of all the various viewpoints on the matter, it’s not easy to definitively pinpoint which perspective holds more sway in the design community these days. But I think it’s safe to assume that a holistic approach is more in line with today’s thinking, which puts UI squarely under the UX umbrella.

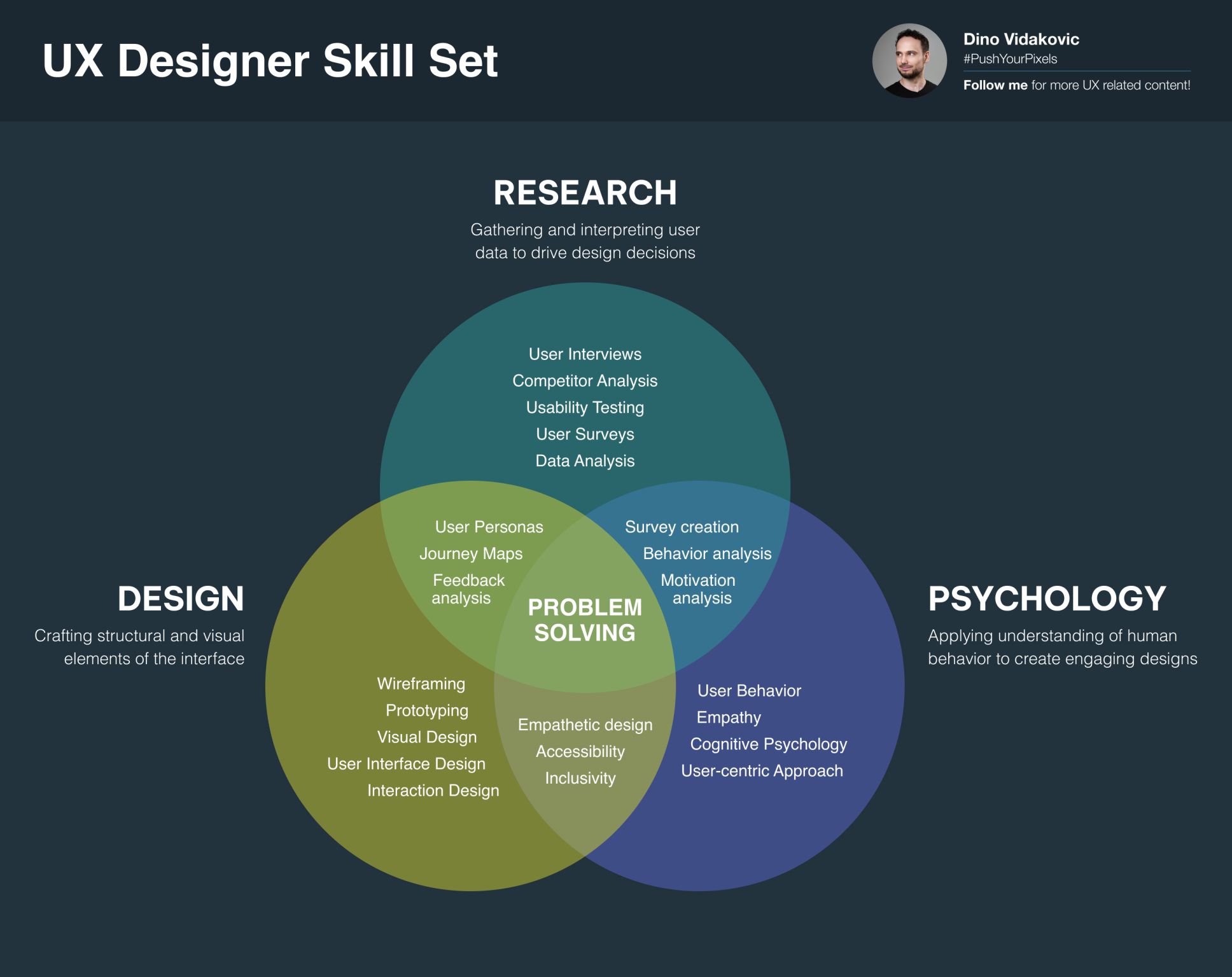

Spoiler alert: as a whole, I’m inclined to agree. More specifically, I look at it this way (and I believe this to be the gist of it all): we designers are problem solvers. There’s a relentless pursuit of understanding. We dive into complex challenges, decipher user needs, and use the insights we gather to come up with solutions.

To effectively do so, it’s best when we leverage a unique blend of skills and knowledge that sits at the intersection of three domains: research, design, and psychology. While each designer tends to gravitate towards certain sectors, the core essence of our work as UX designers remains consistent: it’s all about problem-solving. We research to understand the problem, design to present the solution, and use psychology to ensure that the solution resonates with people.

Practical perspectives

However, for the sake of analysis, let’s challenge this “UI is part of UX” line of thought and instead entertain the idea that they are, indeed, separate. This separation of the two terms is most often encountered in practical contexts, like workplaces and job postings, and it’s primarily based on the notion that UX and UI demand some distinct skillsets and play different roles in the design process.

In practical terms, especially in the context of professional roles within a team, UX and UI can often outwardly appear as separate but closely intertwined disciplines, each with its own specialized focus and skills. However, the exact distinction may shift depending on the context at hand, and many professionals deal with both practical UI and practical UX matters to some degree—especially in smaller teams, where the lines between UX and UI usually become really fuzzy.

Since I generally base my perspective on practical experience, I’ve also noticed that—when they’re free to choose—designers tend to have varying preferences when it comes to what they like to do when they design. They lean towards one or the other, so most often it comes down to UI vs. “everything not UI” (which many would deem UX, essentially leaving UI out of it).

It’s important to note that this isn’t a strict division, though; much like many things in life, it falls along a spectrum. But the difference can be quite obvious, and very rarely do I find designers who truly excel at both. I think this is actually not unusual because UX is quite a large field, and it is only natural that people have certain tendencies or even specializations.

Theoreticizing experience

What about the distinction and/or link between UX and UI when it comes to more theoretical terms?

Perhaps it comes down to how we define UX. How do we conceptualize “experience”, exactly? Does it include the part the user is interacting with along with the experience of using it, or does it only include the experience itself?

Is the car that I’m driving a part of my driving experience, or is it just an instrument through which I am experiencing the driving? Is the guitar that I am playing a part of my playing experience, or is it just an instrument through which I am experiencing the playing?

I think both can make sense. Speaking broadly, UX encompasses every aspect of a user’s interaction with a product, including the UI. Conversely, in a more narrowed-down understanding, UX could be seen as the overall feel and experience a user derives from using a product, while the UI might be considered a separate entity that directly influences that experience.

Ultimately (and rather predictably), the “correct” perspective would largely depend on the specific context, as well as how an individual designer approaches their work.

A couple of philosophical approaches

I’m pretty sure the topic of UX and UI has been pretty much exhausted by us designers by now. To shake things up a bit, I’ve come up with a bit of a thought experiment, if you will. I thought it would be interesting (and decidedly whimsical) to explore some philosophical dimensions that could be applied for a different kind of analysis than usual.

Let’s concentrate on the core idea that a user’s experience is intangible, while a product’s interface is tangible—and whether the interface should thus be considered an inherent part of the experience, or a distinct entity in itself.

Phenomenology

One philosophical lens through which we can examine the issue is phenomenology; understanding the nature of consciousness and experience through the ways we perceive and make sense of the world. In phenomenological thought, the focus is on the idea that our experiences are not isolated from the objects or phenomena we encounter. Instead, the relationship between the one experiencing and that which is experienced is seen as reciprocal and deeply intertwined.

Drawing from this viewpoint, it could be argued that the interface is an integral part of the user’s experience. The look, feel, and functionality of the interface are tied to the user’s perceptions and emotions, which naturally influences their overall experience.

According to Heidegger’s notion of “ready-to-hand”, tools are most genuinely “themselves” when they’re being used and thus become part of our experience. Consider the analogy of playing an instrument. The experience of creating music is greatly influenced by the instrument itself, with the instrument serving as the UI through which the musician translates their intentions into music. The UI in its physical form becomes an inseparable part of the musical experience, and in turn contributes to the musician’s emotions and perceptions.

Of course, this phenomenological perspective is quite an oversimplification (as are the other two philosophical analyses). It doesn’t fully account for scenarios where the UI might not be the sole determinant of the UX; factors like user expectations and prior experiences can also significantly influence the user’s overall perception.

Dualism

Then there’s dualism, as articulated by good old René Descartes, which posits that the tangible and intangible are distinct entities. According to him, the mind, which is intangible, is entirely separate from the tangible body.

In the context of UX and UI, UI would be the tangible entity as represented by the physical manifestation of the product, while UX would be the intangible representation of the user’s thoughts, emotions, and overall experiences. Therefore, from this perspective, the interface and the experience are separate and distinct.

This strict separation doesn’t always hold true in design, as we all know. In practice, bodily discomfort, influenced by the tangible, can definitely impact one’s state of mind; for instance, an uncomfortable chair can contribute to a negative overall experience in a workspace.

The dualistic view might have its merits, but in practical design, the boundary between UI and UX often blurs, especially as modern digital products aim to create seamless, integrated experiences. (Sorry, René.)

Pragmatism

There’s one more perspective I can borrow from philosophy, and that would be John Dewey’s pragmatism. According to Dewey, experience arises from the interaction between an organism and its environment. In the context of design, this would imply that UX emerges from the dynamic interplay between the user and the interface.

From a pragmatic standpoint, the UI could be interpreted as the environment in which users engage with a product or service, and the quality of this engagement influences the user’s overall experience. Therefore, the UI becomes an integral component of the UX, as it directly shapes the user’s perceptions, emotion, and interactions with the product.

Conclusion?

All this philosophical talk underscores the complexity of the UX/UI relationship. In reality, the interplay between UX and UI is multifaceted and context-dependent. These philosophical perspectives might seem like they fit, but they largely oversimplify the intricate dynamics of design and user experience.

So, what’s the real conclusion here? What new insights did we get? If we even did get any, I think it still all boils down to what we already know: designers must recognize that the UX/UI dichotomy is not a static or universally applicable concept. It evolves with each project, product, user interaction, workflow, a company’s internal organization, the job market, you name it. Therefore, relying solely on any framework we come up with to define this relationship, be it philosophical, theoretical, or strictly practical, limits the adaptability and creativity required in the design process.

That said, for the most part, I do think UX should definitely be thought of as the overarching category consisting of many small ones; some tangible, like UI, and most intangible (user research, journeys, psychology, etc). Maybe all we need is a different name for these two—like “practical UX” and “analytical UX”. This wouldn’t suggest that one type of designer lacks any skills but rather emphasizes where their primary focus lies.

According to this naming pattern, all the UX parts would still remain under UX. They would just be separated into two main categories based on the most typical preferences that designers tend to have—practical or analytical. Therefore, they would both be UX designers, but further categorized into Practical and Analytical UX Designers. This might alleviate some practical problems in some instances, for example, when hiring or building a team.

Ultimately, of course, what matters most is the ability to create meaningful, user-centered experiences, regardless of how we philosophically categorize UX and UI.